For a while now, I’ve been busy with the birth of the waltz. It is generally accepted that the waltz came into being around 1750 somewhere in the German cultural room. I use that vague notion intentionally here. Around 1750 the current nation states didn’t exist and with the Seven Years War about to begin, the concept of frontiers and borders became all the more opaque in that area of Europe.

According to some authors, the first mention of the word waltz, to indicate a certain dance type, came from a reference in a theater text “Der aufs neue begeisterde und belebte Bernadon” by Felix Jozef Kurz, who published it in 1754 in Vienna. But even so, the puzzlement about which dance was actually indicated by which dance name when one was talking about a revolving dance in triple meter, remained rife until the end of the 18th century. Dances from the embroiled “waltz family” are called many different names like: Teutsche of Deutsche, Dreher, Sleipfer, Walz, Ländler, Steyrische, etc. Later in the 19the and 20th centuries they will all start to mean different things, but between 1750 and 1800 there is no way to separate between them. The choreographic information in order to do so, is simply lacking. As far as I’m aware and until proved otherwise, no historical dance description that unequivocally describes any of them as a distinct types of couple dances, exists before Thomas Wilson’s first steps in that direction.

Never mind the fact that Wilson was not only publishing his work in London but also is mentioning German and French waltzes, most of us are still bound to believe that the waltz originated from the German countries and got spread from there on out. But based on my recent findings, I start to have serious doubts about the exclusivity of that claim. It could well be that the waltz originally was a German or Austrian invention, but soon after her birth, the dance was probably directly exported and rapidly disseminated internationally. The first description of the paces to execute a waltz turn was again published elsewhere, namely in Paris in 1767 in “Explication des pas de l’Allemagne, in: Almanach Dansant ou Positions et Attitudes de L’Allemande. Avec un Discours Préliminaire sur l’Origine et l’Utilité de la Danse. Dédié au Beau Sexe. Par Guillaume Maitre de Danse pour l’Année 1769. A Paris”, albeit it was meant to be danced in duple meter (take a look at pg 11 to find out yourself). The reason to publish this book was the marriage between the Austrian princes Marie Antoinette and the French Dauphin, later to become Louis XVI.

But there are other early mentions outside of the German lands. The very well documented website Regency Dances presents a thorough appraisal of the British situation. Already in 1762 Giovanni Gallini’s mentions the dance and describes the general outlook “A Treatise on the Art of Dancing”. This Gallini was Italian of course, but had left his homeland to come to London by way of Paris and he was an avid self made man with a well developed instinct for business. He was one of the first to publish a collection of cotillions also in London in 1770 and his treatise on the art of dancing mentions quite a few other dances, connecting their use with certain nations, calling them “national dances”. This wasn’t an innovation as such. Already from the pastoral tradition from the 16th century onward, it was common practice to identify staged dances with the character they had to convey. This identification was purely meant for the theater and mostly or never had any real connection with historical, social or cultural practice in the real world. To think otherwise and try to identify the source of this labeling (i.e. a real dance, belonging to a certain cultural region or room at a certain point in time) often proves highly problematic. The stage was fantasy land and meant to be.

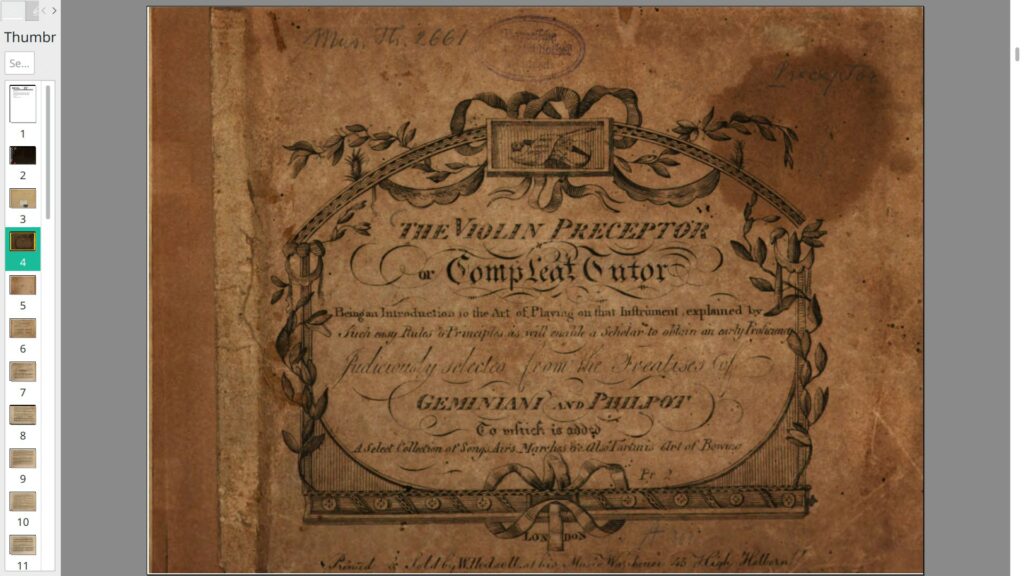

Nevertheless, the waltz and the allemande were linked to the German cultural room in both descriptions. Still, it seems odd that virtually all prints of waltz music appeared far away from this native ground. Early prints of Ländler or Teutsche are known from ca.1790 in German lands. But simultaneously they seem also to be printed in London. But what to think about four waltz melodies appearing in 1760, not mentioning any German country at all? That is what I discovered in the “The Violin Preceptor or Compleat Tutor: Being an introduction to the art of playing on that instrument, explained by such easy rules a principles as will enable a scholar to obtain an early proficiency : To which is added a select collection of songs, airs, marches etc. also Tartinis Art of bowing” again appearing in London.

This is large and by 30 years before waltz melodies appear in print anywhere in the German cultural room and about 47 years before a first waltz ever rolls from the presses in Vienna. At least this indicates that the waltz was already well known outside of Germany of Austria before the end of the 18th century. The influence of the people involved in this publication is obvious. This was already Franscesco Geminiani’s second violin manual. His first appeared – again in London – in 1756 – and was co-edited by none the less by Leopold Mozart. Who in turn, composed a musical fantasy about a wintry sledge ride (Musikalische Schlittenfahrt) in 1754 in which he included a ballroom scene. In that ballroom scene a Deutsche in triple meter is included, one of the first ever uses of a waltz type melody in such a setting. The personal networks of musicians active in a transnational context is probably the best way to understand why waltzes were spreading so rapidly. in 1754 Gallini together with two German musicians, Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, build the Hanover Square Rooms. He would have been thoroughly acquainted with their music by then.

The nice thing about google and the like, is that you can actually find out about such connections directly, 24/24, 7/7, 365/365. Thanks to the immensely important digitization of historical books and archival records, this story becomes better and richer by the day. It is only a matter of time before even earlier mentions of waltzes in other parts of Europe will start to appear. Keep up the good work! All of you. Because without your collective drive to put heritage collections online, my work as a dance historian would be ever so much duller. Thanks you.