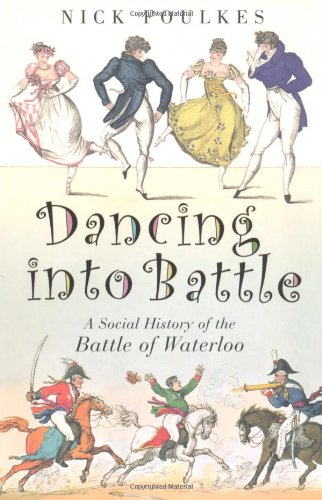

Around the end of last year, I received this noteworthy little book written by Nick Foulkes. The weeks after I read through and through, intrigued more by the title than by anything else, I must confess. It rather seemed one of those typical Britisch history books. The author is well read into the subject, he is telling his story with the adequate amount of passion, and the language is superb some of the time. Bill Bryson is the archetype (although he is an American, stricktly speaking) of this type of historian and perhaps Foulkes is a bit less sexy than him and certainly far less well coached along his way to success.

But, wether this is the kind of history study I prefer, remains to be seen. It’s possible really, that it is not meant as a scientific study. It could, for example, be meant as a written version of the BBC infotainment history news item. If that were the case, one could ask questions about the title in the first place and about the amount of notes keeping cropping up all the time. They, at least, give the impression that one reads a serious study. Which isn’t the case for the whole of the book in my opinion.

The point is of course that the number of Waterloo drenched books and articles in the Anglosaxon world is impossibly enormous. With the years approaching the magical number 15 it hardly could get any worse one hoped. Unfortunately it got tenfold worse. And most of this so called “studies” are just citing each other like an eternal circle of historical life. The reason for this isn’t hard to imagine. Like Foulkes most of the authors don’t bother diving deeper into the archives to look for new insights than strictly necessary. Most of them just read through the masses of published eyewitnesses. The number of these is so scaringly huge, one could ask the question if not every handwritten letter or diary of the 1800 – 1815 years has been printed today.

This fact gave birth to an entire legion of discourse historians, who just love to read all this stuff and dive up for us, the readers, all but the best quotes and oneliners. Because, this writers where there at the time, weren’t they? Which of course is highly discussable. Just like today an eyewitness isn’t everywhere all the time. So, if you would want to create an overview of a certain situation, citing them can be quite challenging.

Of course personal acounts of any kind are much nicer to read that piles of boring archive dossiers. So for the historian who likes to read much, it certainly is an option to run through all those letters. Although they don’t provide answers for everything IMHO. And this book proves just that by making some very bold statements and by comparing a bit boringly the reports of some eyewitnesses. The chance that two eyewitnesses agree on every point of a situation they witnessed is close to zero. But is that so interesting to me, the reader? Aside a funny discussion about just that problem, which can be a sporty thing to do among historians (or other freaks), I strongly suggest not to repeat this trick in front of an audience who bought the book for casual reading.

I just give an example of one of the bold statements. Foulkes marvels quite a bit about the more than liberal amounts of alcohol consumed by the male part of the population in the regency era. Next he states that alcohol was the fuel of the era, unlike later in history. I don’t like the kind of reasoning personally. You could do this of course, but only after a serious investigation and comparison to other era’s. Wasn’t everybody drinking as much before? Isn’t heavy drinking typical for stressfull situations like pre-battle tension? How about the drinking habits among soldiers in Flanders Fields for instance? Or football hooligans today, for they go to battle too, aren’t they? I mean: is this statement based on some hard socio-economical evidence about alcohol production? If that were the case, I didn’t find the kind of study (if it exists) mentioned in the bibliography. Or medical inquiry or insights for that matter? I don’t think so either.

So that been said, the link between the title and the content isn’t always clear to me. There is very little to none to be found on balls in the book. Except for the legendary ball of the Duchess of Richmond on the eve of Waterloo of course. But that is already so thoroughly described and analysed time and again, that it would have been much nicer not to hear from it again. There were other balls in Brussels at the time? Why not dive a bit deeper in them? It is of course nice to learn some new facts about the British war tourism on the eve of Waterloo in Brussels. But I doubt if that was something new as a phenomena. One could write a similar study about Vienna on the eve of the battle against the Turks, I suppose. War tourism is a reality quite well accepted among historians. As long as the tourists stayed a bit on the side, it was accepted by the warlords until the first world war. One could even ask the question if contemporary war correspondence isn’t close to be an historical equivalent.

So my conclusion: nice little book, but not rock solid from an historical point of view. And a very wrong title for someone longing for more insight in ball culture like me. Of course I’am aware that I’am a rather bizarre kind of character among the readers one would like to write for.