Because of the preparation of a guided tour around Leuvens’ dance palaces of the past I needed to dive in my beloved archives again. The tour will take place on the 21th of December and is part of a larger event in our local Cultural Center, celebrating the 10 years aniversarry of folkband Naragonia. Because it was since this spring that I visited the archives, I needed to run through my early findings again first. Distance can be a good companion sometimes in so far it helps you shaping different views on the same subject. Sometimes ideas unconsciously ripe or new insights are born just by waiting a while. I think my brain functions more or less like a Harry Potters’ pensieve, just needing some time for the obvious connections to settle.

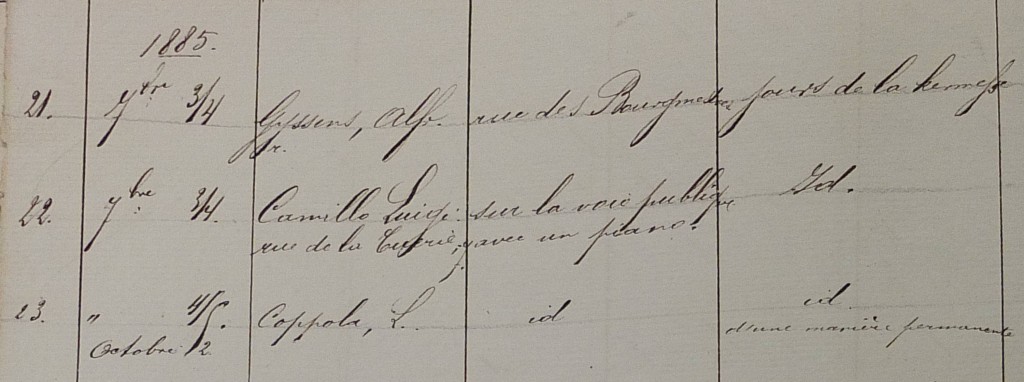

And so luckily I stumbled upon this quote from the registration books for public dances. The series runs from 1875 to 1903 and gives us a unique insight in the distant world of dance halls and popular balls. The registration is probably due to a new community law (I didn’t find out which yet) on public dances from around 1875. For the year 1885 it clearly says:

“L. Coppola – Sur la voie publique avec un piano – Rue de le Tuerie – de façon permanente”

Translation:

“L. Coppola – On the street with a piano – Buchers’ Street – Permanent permission”

I must say that the very fact didn’t in so much surprize me.

All in all, the existance of the registers or the quote in itself didn’t surprise me at all. In most Belgian cities around the period one will encounter a progressively strickter legislation on public balls. In a series of articles for the Mechamusica Bulletin, I put forward the hypothesis that this phenomenon was due to the rather explosive growth in the numbers of dancehalls equiped with mechanical dance organs around the same time. To give a concrete example: in Antwerps’ Kloosterstraat (Abbey Road) there were no less than 14 dancehalls of which 11 were equiped with such a dance organ. The number of riots and troubles this situation provoked should not be underestimated.

Hence the last few years I discovered very similar registers in varioius other city archives around the country. At first glance they provide us with a sheer endless amount of data for the study of public balls. In practice, the information proves to be nonetheless fragmented. At least when one would like to construct a general view on the matter. A ball – following the laws of the time – being public only if:

a) Everyone could attend by bying a ticket

b) It was as such publicly announced and noted down in the register

Balls given by governments or associations were not considered public by most city laws. The first, because they generaly were for free, the latter because only members and their family could attend. Not every city law was an exact copy of the other of course. In this situation, however, I have serious doubts whether the law was strickly applied. I seems rather unrealistic in my opinion, for instance, that in a student city – as Leuven used to be and still is – there only occured 28 balls for the year 1885 as the register shows us. At the time Leuven counted no less than 18 dance halls within its historical walls. So one can imagine that, if the owners had to make a living out of balls alone, this couldn’t be sufficient at all.

But then again, what did the illustrous Mr. Luigi Copolla seek around in Leuven in 1885? As the records state, he worked side by side with the even so illustrous Mr. Luigi Camillo (was he a forefather of the famous Don Camillo?) playing his piano in the streets surrounding the official buchery (nowadays an Aldi supermarket). The piano meaning evidently a pianola type of instrument the time and circumstances being. ‘De façon permanente’ means that both Italians were a kind of street musicians by profession and obviusly recognized as such by the city counsil.

To be frank, Italian street musicians weren’t a rarity in our streets around 1885. They often were the vanguard for their families planning to move to the United States. To scramble the money to pay for the steamliners they often worked as musicians.

Of course the whole genealogical tree of the Copolla’s isn’t known to me, but strangely enough, Francis Ford Copolla’s father used to be a professional musician. He, for instance, composed the wedding music for the scène in Godfather I. A typical Tarantella if you ask me and the fact he knew this music so well, perhaps shows that his for-forfather once played the pianola in the streets of Leuven.

To be continued…