I visited London some weeks ago. Just a short city trip with my spouse. As always, I kept my eyes and ears wide open for rumours about old dance- or music halls. A spontaneous chat in a pub informed me about the illustrious Wilton’s Music Hall. A short search thereafter (I love wifi!) got me acquainted with the lovely website. I sent an email straight after that. No reaction whatsoever. Not even after days. So I plucked up courage and knocked down the door.

One of the more fascinating things about London is the overwhelming amount of signs. You simply can’t turn around anywhere without facing one, wherever you are. Combine that with the typical British heritage genes and you got an official road sign indicating Wilton’s Music Hall on the corner between Graces Alley and Mint Street.

I can’t remember anything of the kind around the corner from that other ‘famous belgian heritage theater project’ called ‘Roma’ in Anwerp. It just makes no sense to compare either. Antwerp isn’t even remotely the metropolitan area it pretends to be even in its wildest dreams. The difference with London was in this case obvious from the start. For example, I had to think twice from when, where or what, but I unconsciously knew Wilton’s years before I entered it. Then it popped up in my head that I must have been by that album artwork of “Burlesque” the second Bellowhead album I reviewed ages ago for a notoriuous Belgian folk site Folkroddels.be (folk rumours). Add to that the fact David Suchet, himself (he just IS Poirot, you know) allowed to use his name to create leverage and awareness about this place and you crash down somewhere in a no man’s land inhabited by Agatha Christie’s specter and a Grade II* heritage detective story.

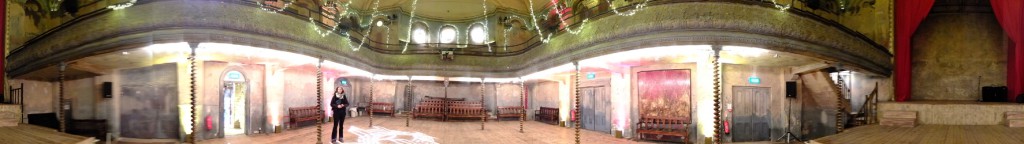

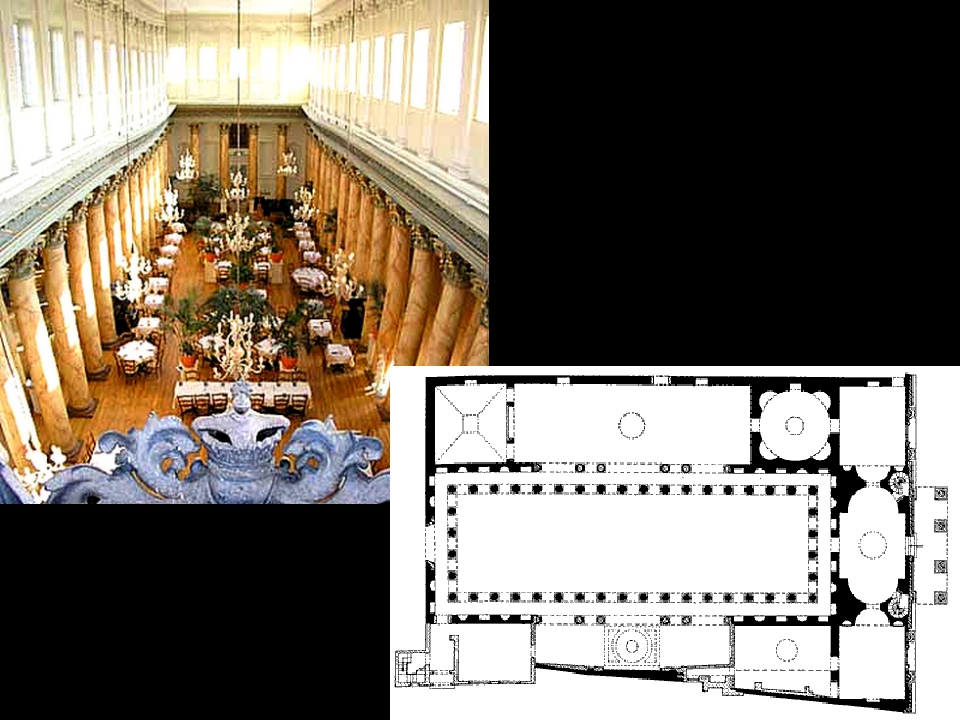

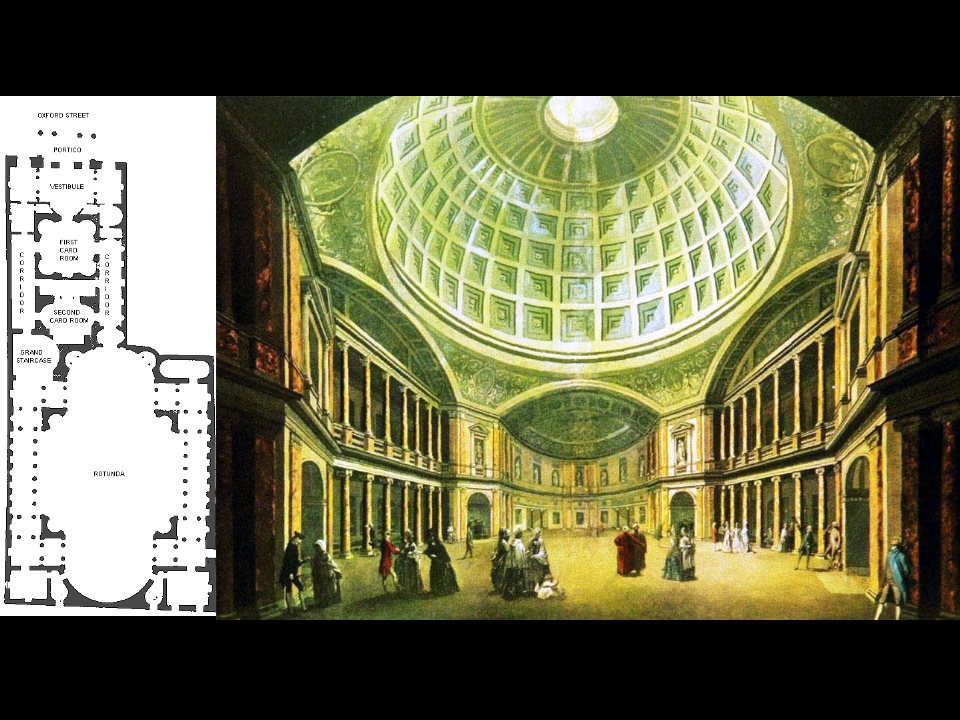

Following this Wikipedia Wilton’s insert the place was erected around 1859 by a certain Mr. Jacob Maggs. After the 1877 fire it got re-built and later on, a Methodist mission ran a social care centre from this devilish place. From there it was closed down, changed into a rag shop of some kind and eventually enlisted for demolition like the rest of the neighbourhood in the ’60. Typical story really. Only the cinema phase lacks and luckily it does, otherwise the original interior design would have been wiped out ages ago. Pillars seem not to go well with an undisturbed sight on a white screen. So, simply put, because of its naked existence, in case of Wilton’s, one can speak of a mere miracle. But, don’t be fooled. It cost Peter Sellers one of his many injured limps to prevent it from being ravaged prematurely as one of the last historic venues of the legendary East End.

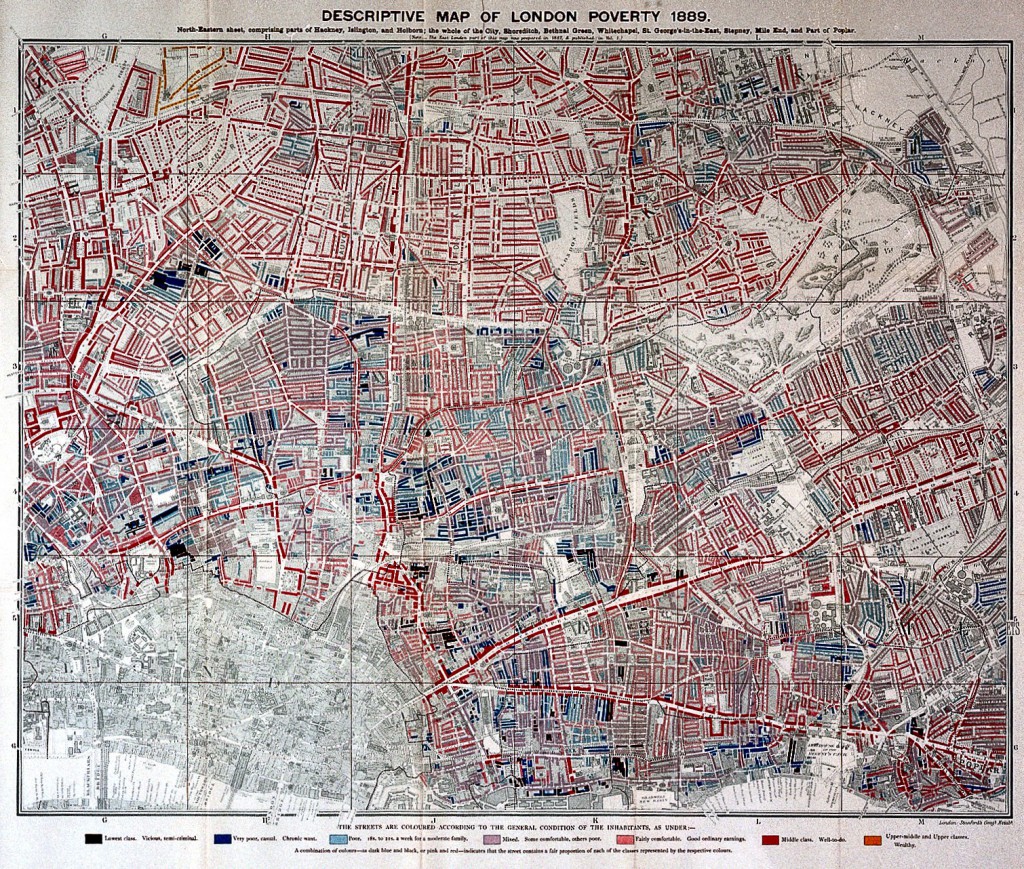

The reason behind this scandalous lack of heritage vision in the past, was inspired by the tinkering of some progressive British minds wanting to upgrade whole neighbourhoods in one stroke during the golden sixties. Which they didn’t succeed in lucky enough. On the contrary. Poverty ended up even more entrenched in the same areas it already existed for ages. You can actually verify that factually, by the way. Only days before, I stumbled across Charles Booth’social maps of London in the London City Museum he created between 1886 and 1903. They are now digitised and ever so appalling a sight as always: in a century nothing really changed. You can see it with the naked eye. Nightmare.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Descriptive map of London poverty, 1889 (north-eastern sheet)

Life and labour of the people in London

Charles Booth

Published: 1892 – 1897

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

How’s that? I you dig a bit deeper into London reality you soon enough discover how. In London there is no such thing as a well functioning real estate market. The real property, the actual soil that is, still is in the hand of government and a handful of families stemming from age old gentry or nobility. The richest man in U.K. doesn’t create jobs in any way. He just owns a few acres of London Metropolitan Area next to Regent’s Park and that’s all. He didn’t do anything to own it either. He just was born in the right place and time and inherited the whole asset. The place still can be fenced out any time of the day and is indicated by black cast iron poles and rolling fences.

Buying a house like we tend to do massively in Belgium, has become virtually impossible in London. You lease the place for 33 or more years. After that it returns in the hands of the original owners. Basically, this means that the price of any real estate is defined not by demand or market, but more likely by a very small group of owners. Considering their factual dominance they probably can be expected to tend to defend common interests (very similar to what trusts of cartels do).

No wonder real estate prices remain sky high. No wonder Pikety and the like consider real estate as the most resilient form of financial capital in terms of anchoring inequality in any society. It is a rather interesting illustration British society still misses some of the benefits of the French revolution: the expropriation of church and nobility enforced by the fear of the guillotine!

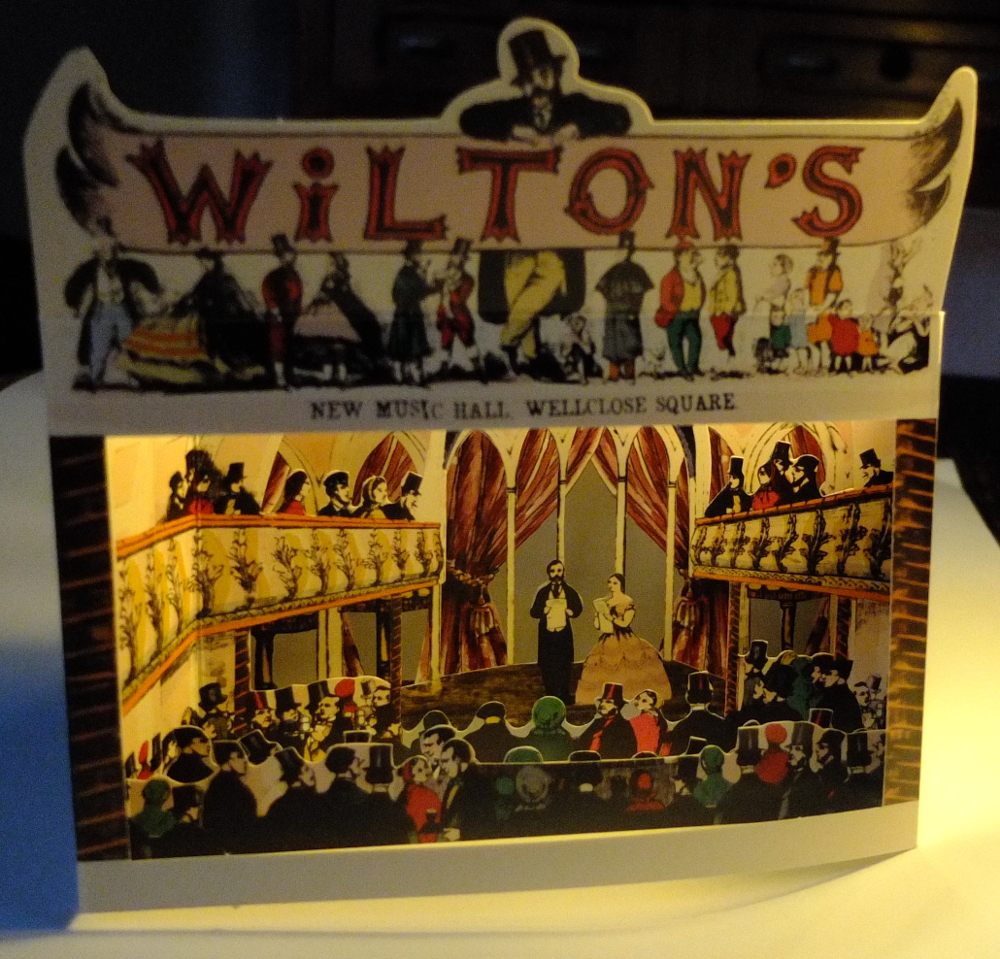

But disregarding these afterthoughts, the place possess a rather fascinating interior design. Beside that, the whole project actually is interesting for any visitor from the continent as it illustrates neatly the way the Brits manage heritage projects. They are king in crowd funding anyway. By sheer coincidence I scored a printed pop-up model in a commercial toy shop in Covent Garden. They also sold towels there, printed over with old theatre posters from Wilton’s and in the shop of the venue we stumbled across cups and even more exotic gadgets. The booklet recounting the history of the place was sold out, otherwise I surely would have fetched it straight away.

Thinking over all this on my way back, I stumbled across a street party at Euston Road. These guys were launching a project to actually re-erect the original entrance arch of the most ancient of all railroad stations in the world. By sheer coincidence, I blogged about this mythical place last year/. As a volunteer only recently discovered the original building blocks dumped into a river, it was hight time to undo some damage of the past. Impossible? Madness? I don’t know. But I do know the British and I wish them all the luck. The actual disaster in terms of architecture, dating from the sixties, will possibly be demolished in the future. Most likely because it never properly worked anyway. So momentum to give back to the British railway heritage some of its glorious past might very well be near. Hope they got some press coverage. You know, only five minutes of political courage is all there is needed…

To be continued for sure…