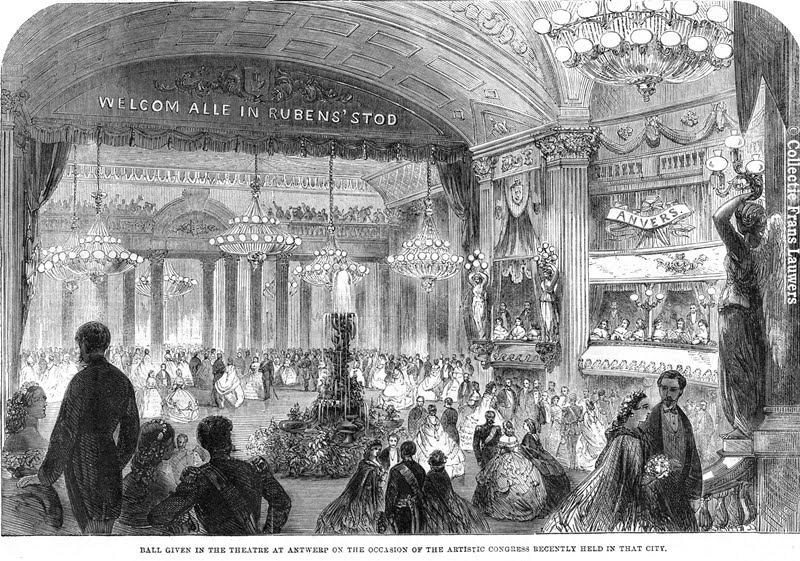

The ball of 20/08/1861 took the stage in the Antwerp Variété Theater as is clearly shown on the above engraving. This imagery was published in the London News of 30/08/1861, proving contemporary digital editions sometimes aren’t that much quicker. Besides British interest, eyewitness reports from Holland and France are known to exist, having been published the year after the event.

This type of international exposure obviously was quite rare at the time. But what do we actually know about the venue framed here? The Antwerp Variété Theater was build in 1829 to temporarily replace the demolished city Opera which had to be rebuild by city architect Bourla, but which only opened in 1835. That the temporarily construction would survive until 1898 was far longer than originaly expected. The nice thing about this theater is, that it happened to be a sort of public-private enterprise of its time with on one side the city government and on the other side a proficient enterpreneur. The witness of which one can consult today in the city archive of Antwerp. The papers offer a unique insight in the venue’s exploitation.

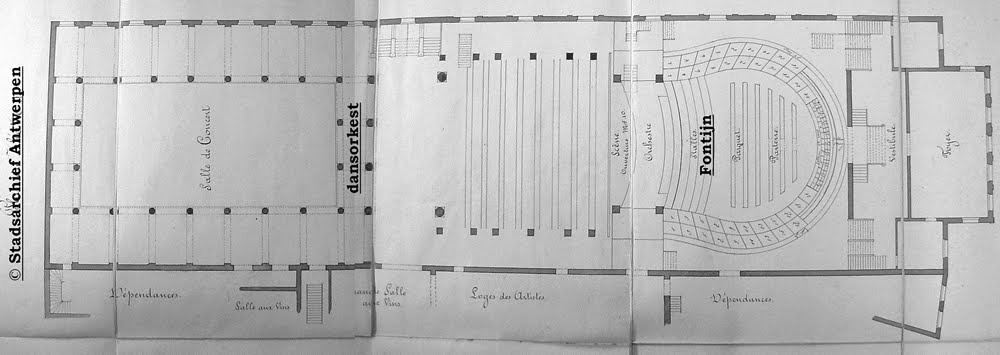

Digging through the papers I unearthed this particular plan proving the Antwerp Variété to offer a classic Italian theater layout (horse shoe), embelished with a vast foyer at the street side. Just as in the opera of Ghent today, visitors could arrive safe and dry in their carriages underneath the foyer and swiftly enter the undisturbed peacefull variété world.

A remarkable feature, nevertheless, is the continuation of rooms behind the theater scene as is clearly shown on the engraving and the plan alike. Needless to say, this spacious construction offered vast possibilities for large scale events like the one of 1861. Virtually every European theater venue of the 19th century disposed of a ballroom construction that could be set up covering the parterre and orchestra pit, leveling it with the scene, thus shaping a vast dance space. In this particular case, the dancefloor was enlarged by the rooms behind the scene, a feature I consider a novelty regarding it’s construction around 1829. I personally am not aware of any similar theater layout in Europe before 1850, even not in London, Paris or Vienna, considering the lively ball-culture of this capitals in these days.

Unsurprizingly the Antwerp Variété Theater offered a multi-functional theater space, albeit a bit ahead of its time in the way it was conveived. I can’t deny that I suspect this building to have stood model for the Vlaamse Schouwburg (Flemish Theater) on Kipdorpbrug that opened in 1874. Notice for instance the very strategic emplacement of the orchestra, yards above the dancefloor. Johan Strauss Jr. would have loved the spot, perched as an eagle high above the dancers. A position causing some practical problems I will return to later in this series.

Images:

Interior Variété Theater:Courtesy of Frans Lauwers Collection

Floor plan Variété Theater: Stadsarchief Antwerpen MA#8811

Flemish Theater: Oude Postkaarten

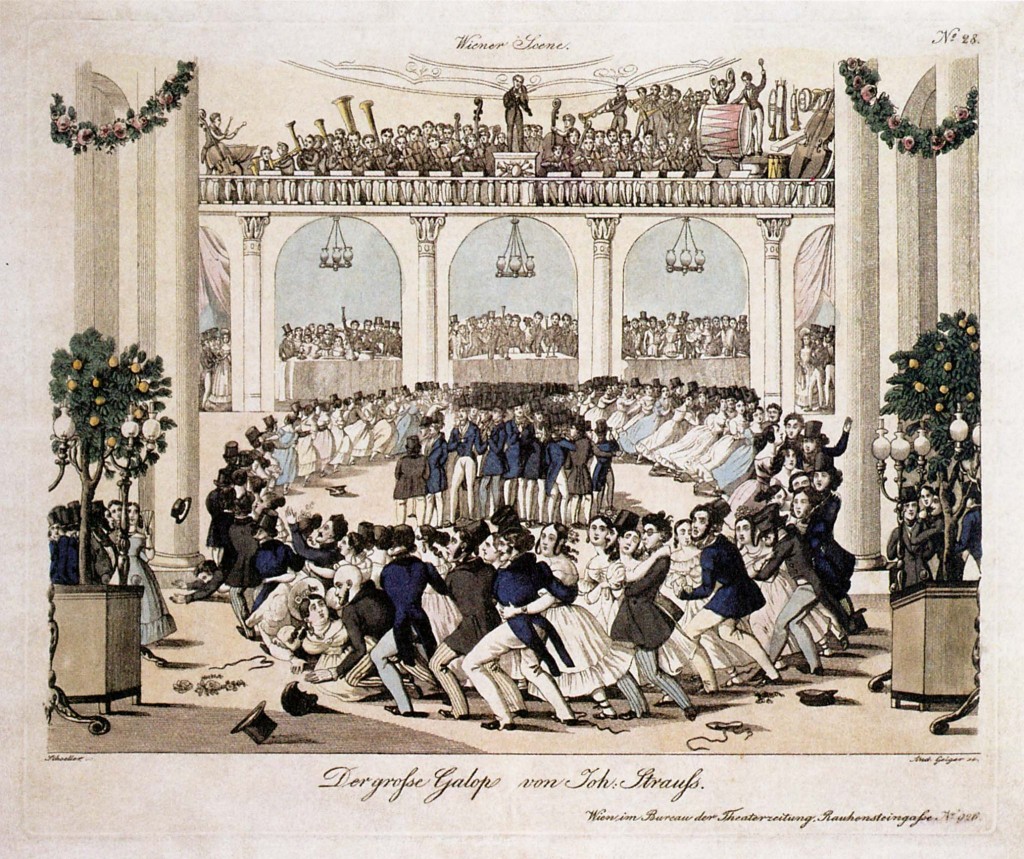

Strauss: Wikimedia Commons