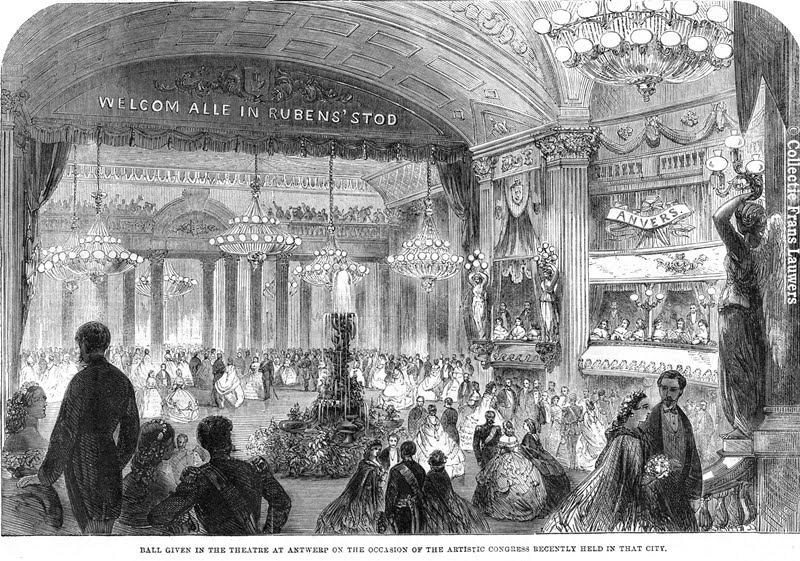

What makes the ball from 20/08/1861 so special, it seems, is the fact that one can unearth so many details offering a unique insight. In previous posts I discussed the dance programm and the venue, but believe it or not, there even exists an eyewitness account. A certain Harry Peters edited an article about the Kunstfeesten (art festivities) and issued it in print the next year (printed by J. Jorssen). The events must have made such an impression on the minds of contemporaries, that there was money to make, even a year aftewards.

Peters opens his account with an unusually detailed description about what at the time was meant with ‘paré’, the term used in the ball’s programm:

“The gentlemen had to be in evening dress, the ladies ‘en toilette’. Which means that members of the male sex had to have a spiering with black dress and white collars, and the crinolines were not allowed without their hats; they had to be coiffed.”

For the ladies, the picture above from a fashion review of 1860, offers a striking similarity with the dresscode from the drawing I used in the second part of this series. De design of the Crinolines, dresses using endless layers of cloth, changed considerably around that time under the influence of the English king of fashion at the time – Worth. The heavy wooden cage suporting the layers (a.k.a. the farthingale), was replaced by a much lighter one made of leather and whalebone.

The question I continue to ask myself is: how on earth could ladies dance with such a massive dress? The polka’s and walzes would of course never become very swinging indeed. The reason why the farthingales pronounced the ladies backsides so much can perhaps be explained by the fact that in this manner, one could a least approach them from the front. But just imagin: corset + fathingale on a hot summernight in August? No thanks!

For the gentlemens dress, the term ‘spiering’ made me suffer to digg what it meant. Even variants like ‘spearing’ or ‘speering’ don’t give any results related to dress code when you would try them on google as I did. But if we can believe the truthfullness of the picture from the second part of this series, it must have been a kind of tuxedo’s with tails. The prominent military uniforms are also eyecatching and remind me of their equally dazzling presence in Luigi Visconti’s ballscene from Ill Gattopardo.

Following Peter’s account, the venue was ornated more exuberantly than on previeous occasions. Rare plants were used to contrast wonderfully with the goldened statues, some of which were by the neo-classical sculptor Antonio Canova (1757 – 1822). I guess they were copies from the Antwerp academy at the time, because no Canova’s are known to exist in any of the Antwerp Musea. Allas, the copies of the academy were destroyed during the sixties, when the contemporary art scene believed them to be academic bourgeois art. People can be really blind, believe me.

And as Peter’s account continue, I found out that the fountain in the middle of the dance floor actually would have been a kind of perfume dispenser. On the far end of the venue used to hang an enormous mirror reflecting the dancers and illuminating the whole room. Even the name of the conductor, who you can discern perched high above the dancers, is mentioned. P. Houben would have been probably the conductor of all the ball’s of the season, as it was customary in the 19th century to engage orchestra’s on seasonal basis. I couldn’t find much information about this Houben. There used to exist a painter with the same namen, but it was a Henri (1858 – 1931) who was known to have been a violist first, before switching trades. And if I start freewheeling completely, I must of course think about the famous Belgian Jazz saxophonist, Steve Houben who is known to to stem from an Antwerp artist family. If any of you knows more about the Houben family, I’am alway’s interested

An overview of all the articles in this series, can be found here