Sometimes one has to reconsider a previous insight. A long, very long time ago, somewhere around the year 2007, after a strenuous and painstaking effort, I developed the concept of the “basilica – type” for entertainment venues (in this article). Nowadays, the use of the concept has become fairly common among art-historians acquainted with interior design, but at the time, I was, I believe, one of the first to call it that way. And I certainly placed it more central in the developement of an authentic civic entertainment achitecture in the 19th century.

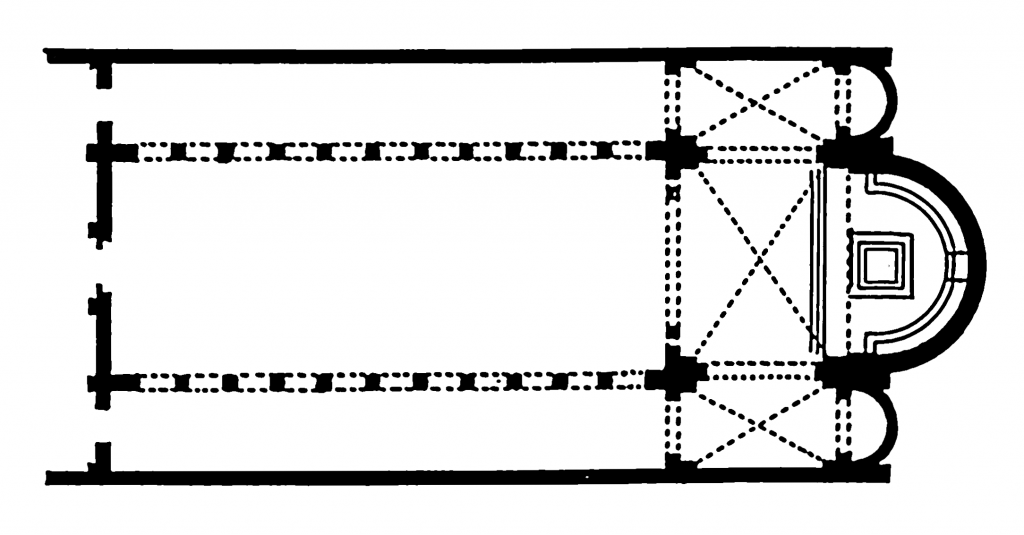

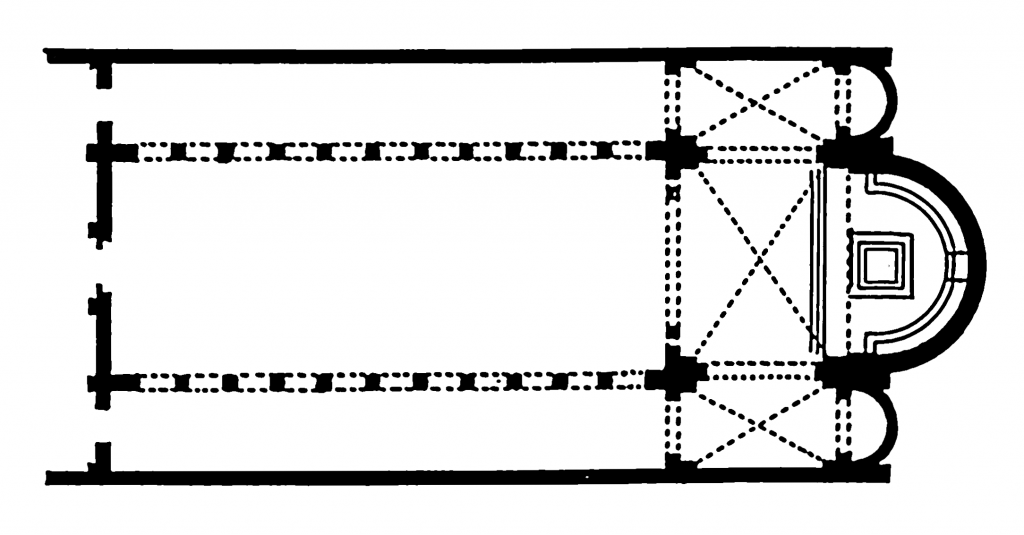

Back than, I toiled in the sweat of my brow at the research of the dansant project, after which this blog has been named, by-the-by inventorying all planning permissions for dance halls in the Antwerp city archives. After some weeks at this, It gradually grew on me, that virtually all these venues basically were based on the same layout, from the earliest to the most recent. Strangely enough, it appeared to be very similar to the nave of a classical church. By then, as I had truly digested my university readings about the developement of church architecture, I knew that the eldest form of the nave came from the roman basilica. And so I decided to baptise this type of floorplan for dancing halls, the ‘basilica-type’.

At the time, I hadn’t the faintiest idea that 19th century contemporaries also called it that way. But what I did understand, was, that, even if the idea sounded good, you don’t run far with it in contemporary academics when you don’t underpin it with enough hard data. So, there I was, searching myself silly, reading each and every 18th- and 19th century art treatise on architecture I could lay my hands on. Along the way, I learned a great deal about the building of churches and palaces, but for no particular reason, no one seemed to really care about dancing halls.

Next, I tried to find out where the earliest dancing halls in Europe had been built. From the start, I considered Great Britain the best option. There on the other side of the channel a civic type of concert life emerged, so much earlier than here on the continent, as we were only getting at it around the beginning of the 19th century. Basically, my idea was, that, if, by any chance you looked at a similar tender for a building first, in the end you possibly would land with a similar concept.

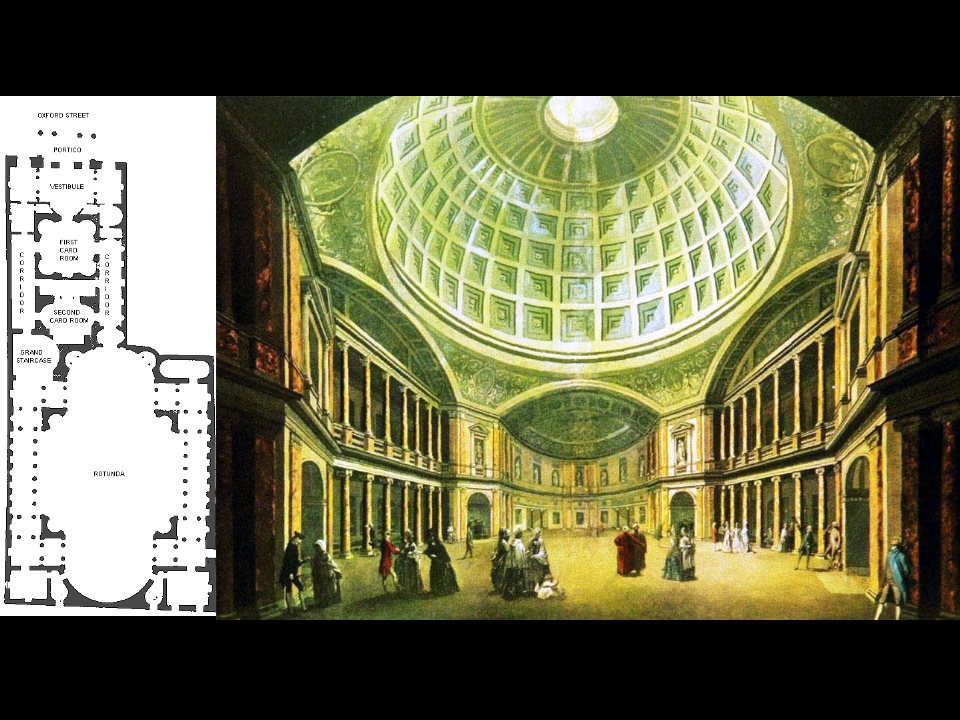

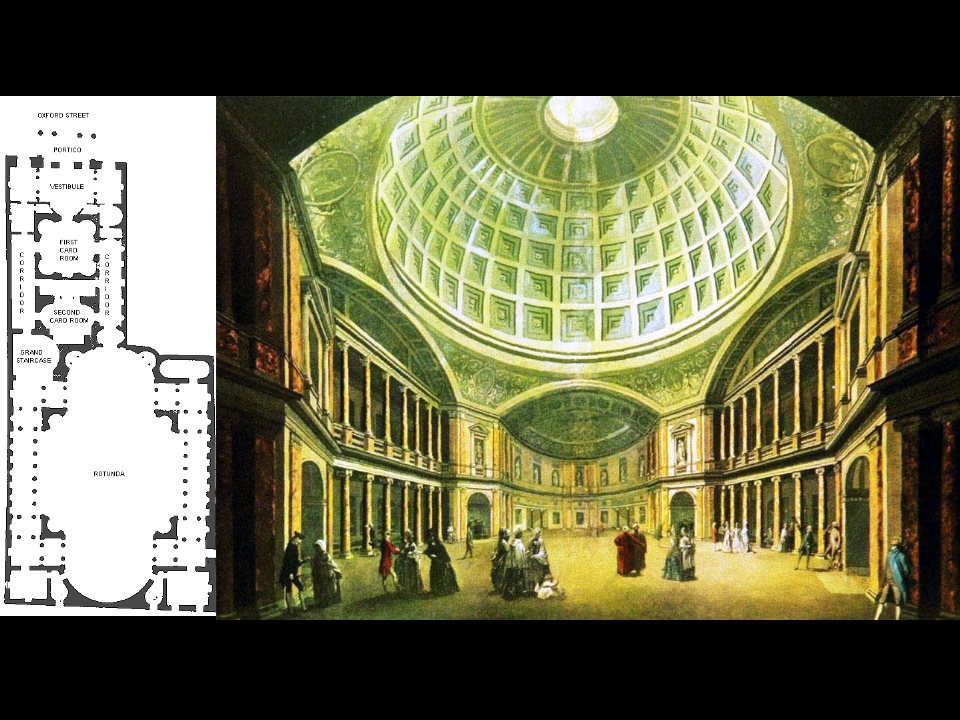

This idea turned out nicely, because just as the Italian horseshoe theater type was derived from a Greek classic example (Delphi), for this inovative type of concert- or dancing halls, they also went looking for classical examples. First, some quite exotic styles were tried, without much succes. Or, what to think about – the nowadays vanished – Pantheon venue on Oxford street, London, based on the Hagia Sophia? The eldest example, by far, I could discover was the – still existing – Burlington Room in York, from 1732, based on the Greek Parthenon.

But, despite this early exotic attempts, the building guild soon stuck with the basilica floorplan and never looked back. So, why the basilica one may ask? My best guess is, because of a combination of factors. As a first, the roman basilica, originally – and it was certainly branded so by renaissance cultural thinkerers – can be considered an early civil building type, used for trade and jurisdiction. It clearly wasn’t a religious temple – it became so only after christianism took over – neither had it any military function, and it certainly was no house to live in. So, gradually, the basilica became the symbol of the civitas, the seat of civil power, a thing the enlighted folks of the 18th- and their 19th century brethren, longed very much for.

So, when you needed a building for public gatherings were we, the citizens could meet on foot of equality, the basilica offered a compelling proposition. To begin with it has a flat central floor and there aren’t any hierarchical positions like the boxes in the classical opera houses. But, yet, there are other motives, among which, the economical motive stands out in particular. The basilica concept offers – technically speaking – an easy solution to built over wide spans. And technically simple building solutions, eventually, tend to turn out cheaper than complex ones. If you want to exploit a building following a commercially viable scheme, you want to build quick, cheap and reasonably safe. Nice to know that even expensive windows – as in a church – aren’t required in a dancing hall. Most entertainment there takes place at night in the half dark anyway. When the cast iron industry starts to deliver high quality building elements like pillars and spans, the tap shot out the barrel completely. The only thing you had to do, was cast your pillars and spans somewhere and bolt them together like a meccano on the building site. Thinking of it, the practice compares beautifully to the way of setting up huge factory halls.

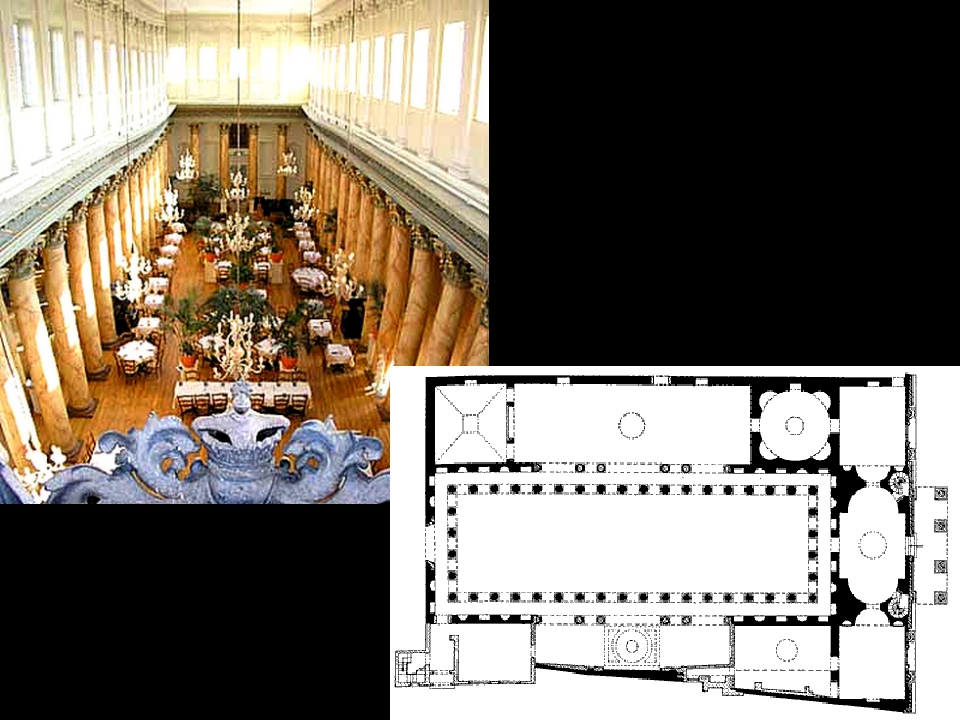

An last but not least, the basilica-type use of space is potentially highly profitable, because you can rent the room out for concerts, dinner or tea parties and even balls, and several timeslots a day if you want. So, commercially speaking, it works like a charm when you want to combine or reach different kinds of public. Being so versatile, basilica-type buildings developed into the standard for variety theater venues in the course of the 19th century and cinema venues later on. Only when the law forebade the use of loose chairs in cinema’s in the years after the first world war, the owners had to make hard choices: variety show or cinema. And because it turned out to be cinema most of the time, the sledge hammer fell regularly. That’s the main reason why you don’t see this building types much around these days: most of them where deliberately demolished for economical reasons already a century ago. No world war needed in this case. Or contemporary city planning for that matter.

So why I wrote this fair piece of text? Well, because, as I stated in the first few lines of this article, in the course of last year I was confronted with new facts pointing all in the same direction. Until recently, I guessed that the basilica-type only got foot on the ground here in Belgium, after the French revolution, at the beginning of the 19th century. The earliest example, I knew off, was the Société Philharmonique d’Anvers, erected in 1813, on the spot next to the Arenberg Theater in Antwerp, where the actual Theatre Hotel is situated. For me, that was the start. Recently, I read the remarkable book on the Frascati Theatre in Leuven (Belgium), built in 1807 and designed by Architect C. Fisco (the one from the College De Valck in Leuven and the Martyrs Square in Brussels). The Frascati definitely pbviously had the basilica layout already some years earlier, but it was still after the French rushed in.

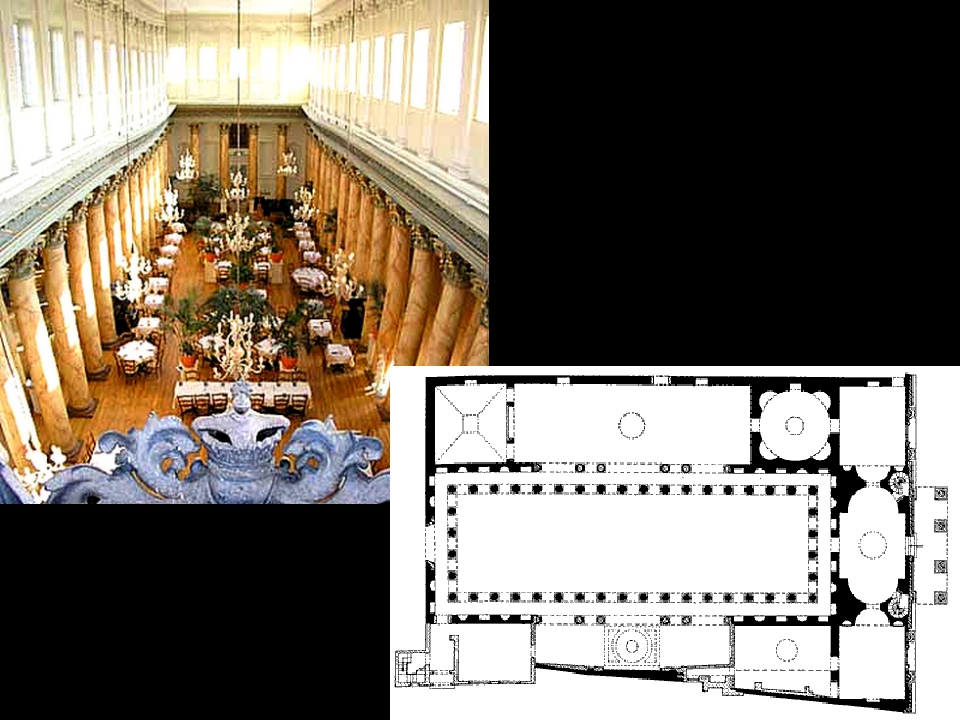

But last week I discovered Xavier Ducennes’ beauty of an article about the Concert Noble (Nr 37, pg 81), a nowadays disappeared concert hall in Brussels, constructed in 1779, and to my knowledge the very first example in Belgium of basilica-type achitecture applied to a concert hall. But not only it came as a shock to me, but Ducenne refers to the Burlington Room in his article and also to the Pillars’ Room in Felix Meritis in Amsterdam, built in 1777. Amsterdam? That’s damn close to Brussels and definitly on the continent. So, perhaps there is much more at hand. IMHO there is a rather fascinating genetic filiation at work here, making me dream of a European wide project about the developement of civil entertainment architecture from this type…

For sure to be continued…

Images:

– Wikimedia Commons

– Crié Antwerpen – Distrifood

– Zuilenzaal – Felix Meritis